A factory turbocharger is engineered to survive 150,000 miles. Yet I've seen them fail at 60,000. I've also watched track-day warriors push the same turbo past 200,000 without a rebuild.

The difference? It's not luck. It's not even driving style. It's understanding what actually kills turbos and what doesn't.

Most advice you'll find online is recycled forum mythology. Let me set the record straight.

How Long Should a Turbo Actually Last?

Modern turbos are built to match engine lifespan. Garrett, BorgWarner, and IHI design their units for 150,000 to 250,000 miles under normal driving conditions. That's the engineering target. But "normal" is doing a lot of heavy lifting here.

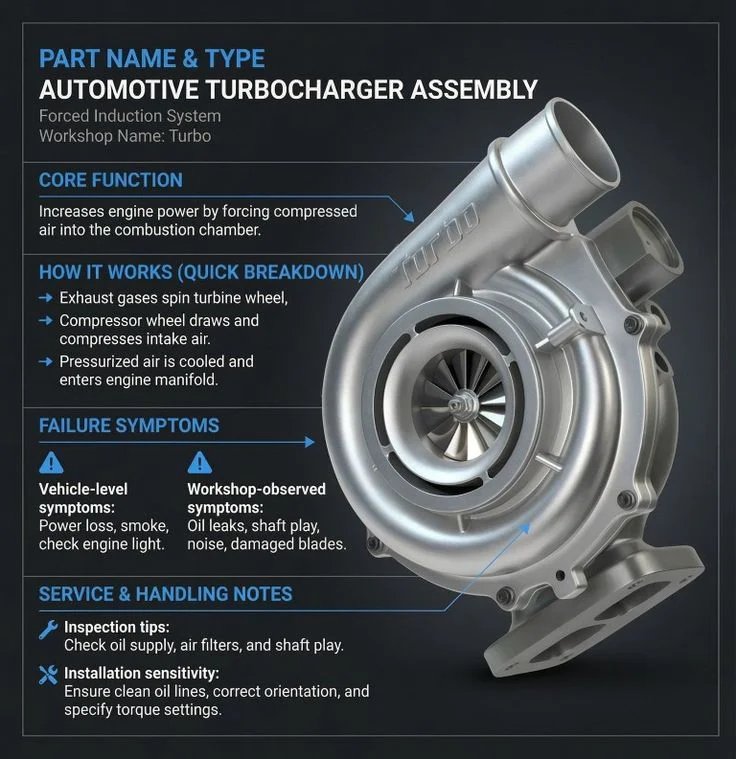

I've torn down turbos that failed at 50,000 miles. The common thread? Oil starvation, contamination, or heat abuse. A turbo spins at up to 280,000 RPM. The shaft floats on a microscopic oil film thinner than a human hair. Mess with that oil supply, and you're on borrowed time.

Here's what actually matters: oil quality, oil change intervals, and how you treat the turbo during thermal extremes. That's it. Everything else is noise.

The Idle-Down Myth: Do You Really Need to Baby It?

“Let the turbo cool down before shutting off the engine.”

You've heard it. Maybe you do it. But is it necessary?

For modern cars? No. Not unless you've been on a racetrack or towing uphill for twenty minutes straight. Today's turbos use oil and coolant passages. When you shut off the engine, coolant continues to circulate passively, preventing oil coking in the bearing. This is called thermosiphoning, and it's standard on nearly every production turbo since the mid-2000s.

Older turbos like those in 1990s Supras or early WRXs lacked coolant jackets. Those needed a cooldown idle. But if your car was built after 2005, idling for five minutes after your grocery run is theater.

Exception: if you've been driving hard, redline pulls, sustained boost, high load……. let it idle for 30 to 60 seconds. That's enough to drop turbine temps and stabilize oil pressure. Anything longer is overkill.

What Noises Mean Your Turbo Is Dying

Turbos don't fail silently. They give warnings. Learn to hear them.

- High-pitched whine or whistle that wasn't there before? That's compressor surge or a boost leak. Not catastrophic yet, but it's a red flag. Check your intercooler pipes and clamps.

- Grinding or rattling on startup? That's bearing wear. The turbo shaft is contacting the housing. You're looking at weeks, maybe months, before failure. Don't ignore this.

- Exhaust note gets raspy or fluttery under boost? Exhaust wheel blades are damaged. Could be foreign object ingestion, a piece of carbon buildup, a failed gasket fragment, something that made it past the intake filter. Pull the intake pipe and inspect the compressor wheel with a flashlight. Look for blade damage or shaft play.

Here's the test I use: with the engine off, reach into the intake and try to wiggle the turbo shaft. There should be slight radial play around 0.001 to 0.003 inches, but zero axial play. If the shaft moves back and forth along its length, the thrust bearing is gone. Time for a replacement.

Can Cheap Oil Actually Ruin a Turbo?

Yes. Full stop.

A turbo is the most oil-dependent component in your engine. It relies on hydrodynamic lubrication at insane speeds. Cheap oil breaks down faster under heat. It shears. It loses viscosity. And when that happens, metal touches metal.

I've rebuilt turbos where the bearing surface looked like sandpaper. The oil analysis showed fuel dilution, thermal breakdown, and contamination. The owner? Using budget oil and extending drain intervals to 10,000 miles.

Use the oil your manufacturer specifies. If it calls for 5W-30 full synthetic, don't substitute 5W-20 conventional because it's on sale. Turbocharged engines generate more heat, more blow-by, and more combustion byproducts. The oil works harder. Respect that.

Change it every 5,000 miles if you drive hard. Every 7,500 if you don't. And for the love of engineering, use a quality filter. A $4 filter can destroy a $2,000 turbo.

How to Reduce Turbo Lag (Without a Tune)

Turbo lag isn't a defect. It's physics. Exhaust gases need time to spool the turbine. But you can minimize it.

Keep the engine in its powerband. Turbos build boost faster at higher RPM. If you're lugging the engine at 1,500 RPM in sixth gear, you'll wait forever for boost. Downshift. Use the gearbox.

Reduce intake restrictions. A clogged air filter chokes airflow. Replace it. Check your intake piping for collapse or blockages. More air in means faster spool.

Fix boost leaks. A loose intercooler clamp or cracked charge pipe bleeds pressure. You'll never build full boost, and what you do build takes longer. Pressure-test the system.

Beyond that, you're talking hardware: lighter wheels, twin-scroll housings, anti-lag systems. Those require money and expertise. For daily driving, just keep the turbo fed with clean air and stay in the right gear.

When to Rebuild vs. Replace

Here's the reality: rebuilding a turbo costs $400 to $800 in parts and labor. A new OEM turbo runs $1,200 to $2,500. A quality remanufactured unit sits around $600 to $1,000.

- If your turbo failed due to age and wear…… bearings worn, seals leaking, a rebuild makes sense. You're replacing the consumable parts. The housings are fine.

- If it failed due to oil starvation, contamination, or foreign object damage? Replace it. The housings are likely scored. The CHRA (center housing rotating assembly) might be warped. A rebuild will fail again within 20,000 miles.

And here's what nobody mentions: if you rebuild or replace the turbo without fixing what killed it, you'll kill the next one too. Clean the oil system. Replace the oil feed and return lines. Check for carbon buildup in the intake. Fix boost leaks. Otherwise, you're wasting money.

The Bottom Line

A turbo will outlast your engine if you treat it right. Use good oil. Change it often. Don't drive like a maniac and shut off the engine immediately, unless your car is ancient. Listen for warning sounds. Fix problems early.

That's the truth. No mythology. No forum science. Just what works in the real world, backed by years of tearing these things apart and putting them back together.

Comments (0)

Please login to join the discussion

Be the first to comment on this article!

Share your thoughts and start the discussion